TL-45-103/79 Update 7

Yad Vashem and the National Civil Cemetery: two places for conserving searing, raw, and painful memories in the State of Israel and the broader Jewish world.

After our group’s usual breakfast together at the hotel, we set out bright and early to Yad Vashem. We went along winding roads, leading up the Mount of Remembrance to the entrance to Yad Vashem. There, we were greeted by Martine, an oleh from Manchester who has dedicated her life to Holocaust education at Yad Vashem. She has educated thousands upon thousands of people, igniting some sort of spark — of knowledge, of compassion, of understanding, of resilience, of hope — into the heart of every person she has guided. We were up next.

It is hard to describe Yad Vashem. It is perhaps easier to just mention some moments. Our group kept intersecting with a group from the IDF, and at one point while we watched footage of bodies being bulldozed into pits, young soldiers alongside us stared with the same transfixed look in their eyes, and the same tears, as well. It was less that we shared common ground. It was that we shared one soul. We learned about the logistics of mass murder and how an entire continent (and world) was conditioned into apathy at best, or enthusiastic participation at worst. But we also learned about the unbelievable spirit of resistance that countless Jewish people expressed even in the harshest conditions.

One of our Israeli participants for the weekend had visited Treblinka some years ago. At the time, he wrote a poem about the experience of walking past mass graves for Jews who perished in the Holocaust. It had torn part of his heart into pieces, but it had also motivated him to pursue a career in the IDF with tremendous pride. What does it mean to say some of us cried at one moment, and some of us cried at another moment? We were all one soul, after all.

It was difficult to move on from Yad Vashem, but Martine had done her work. We had not only learned about the Holocaust, but also taken the time to learn and memorialize some of the people who did not survive.

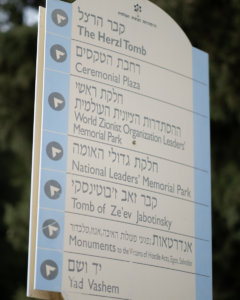

After lunch, we went to the National Civil Cemetery. We learned more about the history of Zionism and the origins of modern-day Zionism as a state-building effort. We stopped at the grave of Theodor Herzl, but rather than ascend higher, it was time to descend down the hillside and into more pain. We took time at the Last Kin Memorial, dedicated to people who were the last survivors in their families after the Holocaust, who then perished fighting for the State of Israel. There was also a plaza dedicated to victims of terrorism in Israel, from the 1800s to the present day. All the thousands of names were inscribed on stone panels: they included Jews, Muslims, Christians, Druze, and more. In some cases, several names in a row shared a single surname, representing attacks where multiple members of one family died at once. Lastly, we stopped at the graves of many soldiers who had been killed while on duty. It was hard to fathom how many families had been ruptured so catastrophically, losing their dearest loved ones. We confronted this harsh reality through testimonies from our Israeli participants about what it was like to lose their friends. Lastly, we honored the contributions of service members by singing HaTikvah, the national anthem.

Our day concluded with a warmly lit dinner in German Colony, followed by free time. We passed through hours of devastating grief, but Judaism and Jewishness is not about pain. Instead, it is about faith, survival, life, birth, memory, and standing for humanity under the guidance of the divine. And with that in mind, as we criss-crossed Jerusalem to enjoy the nightlife, we were practicing the most consistently revolutionary statement In all of human history: Am Yisrael Chai, the Nation of Israel Lives.